Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: RSS

[display_podcast]

Date: June 15th, 2016

Guest Skeptic: Dr. Anthony Crocco is a Pediatric Emergency Physician and is the Medical Director & Division Head of the Division of Pediatric Emergency at McMaster’s Children’s Hospital. He is the creator of SketchyEBM.

Case: A 2-year-old girl presents with a two-day history of vomiting and diarrhea. She is minimally dehydrated and tolerating oral fluid only. You remember reading about the sodium-glucose co-transporter and electrolyte fluids that were initially developed by the World Health Organization for children with diarrheal diseases. You have heard parents ask about just using watered down juice and debate whether this is a viable option for these children.

Background: Gastroenteritis is a common illness in children and these children are at risk of dehydration from inadequate intake, excessive losses or both together. If children are unable to tolerate oral hydration we often have to use intravenous fluids and sometimes require admission to hospital for ongoing fluids.

Goldman et al Pediatrics in 2008 published a helpful table describing the degree of dehydration in children ranging from mild, moderate to severe.

Most cases of gastroenteritis are mild, self-limiting and can be treated effectively with oral rehydration. For more information on visit this site on Oral Rehydration Therapy. The Canadian Pediatric Society also has an algorithm for oral rehydration (see below).

We covered ondansetron on SGEM#12. Bottom line – Ondansetron is an effective anti-emetic preventing further vomiting, intravenous fluids and admissions for children with gastroenteritis.

- NNT of 5 to stop vomiting

- NNT of 5 to prevent one intravenous insertion

- NNT of 14-17 to prevent one admission

We also talked about ondansetron on SGEM#122. For the centers studied, the rates of ondansetron use increased from 0.1% to 42%. However, there was no significant difference in the rates of intravenous insertion or hospitalization during this time frame.

Children with vomiting from gastroenteritis, and mild-moderate dehydration, should have a trial of oral rehydration therapy. Failing this, ondansetron should be administered. Failing that, intravenous fluid should be considered.

Clinical Question: In children with mild gastroenteritis who are minimally dehydrated, is diluted apple juice and preferred fluids as good (or even better) an oral rehydration fluid compared to an electrolyte rehydration solution?

Reference: Freedman et al. Effect of dilute apple juice and preferred fluids vs. electrolyte maintenance solution on treatment failure among children with mild gastroenteritis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. May 2016

- Population: Children presenting to the emergency department between six months to five years age. They needed to have three or more episodes of vomiting or diarrhoea in past 24 hours and symptoms could not have been going on for more than 96 hours. The children also needed to weigh at least eight kilograms and have minimal dehydration on the Clinical Dehydration Scale (CDS).

- The CDS is a four-item, eight-point scale. Children with a CDS less than five and capillary refill of less than two seconds were classified as minimally dehydrated.

- Excluded: Inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, diabetes mellitus, inborn errors of metabolism, prematurity with corrected postnatal age less than 30 weeks, bilious vomiting, hematemesis, hemtochezia, clinical concern of an acute abdomen or a need for immediate intravenous rehydration.

- Intervention: Half-strength apple juice or preferred fluids once they went home (5ml q2-5min in emergency department, then 10ml/kg for each episode of diarrhoea or 2ml/kg for each episode of vomit).

- Comparison: Apple-flavoured, sucralose-sweetened electrolyte maintenance solution

- Those who vomited in either group received oral ondansetron

- Outcome:

- Primary: Treatment failure that consisted of a composite outcome of five things:

- Hospitalization or intravenous rehydration

- Subsequent unscheduled health care visit (emergency department, urgent care clinic, walk-in clinic or office)

- Protracted symptoms (More than two episodes of vomiting or diarrhea within a 24-hour period occurring more than seven days after enrollment)

- Cross over (physician request to administer a solution representing treatment allocation crossover at the index visit)

- Three percent or greater weight loss or Clinical Dehydration Scale score of five or higher at in-person follow-up

- Secondary: Frequency of diarrhea and vomiting, percent weight change at 72 to 84 hours, intravenous rehydration at initial visit or a subsequent visit within seven days, hospitalization at initial visit or a subsequent visit

- Primary: Treatment failure that consisted of a composite outcome of five things:

Authors’ Conclusions: “Among children with mild gastroenteritis and minimal dehydration, initial oral hydration with dilute apple juice followed by their preferred fluids, compared with electrolyte maintenance solution, resulted in fewer treatment failures.”

Quality Checklist for Randomized Clinical Trials:

Quality Checklist for Randomized Clinical Trials:

- The study population included or focused on those in the emergency department. YES

- The patients were adequately randomized. YES – Block randomization (Blocks = 8)

- The randomization process was concealed. YES

- The patients were analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized. YES – Intention to treat analysis was done

- The study patients were recruited consecutively (i.e. no selection bias). NO – Convenience sampling (6 days/week, 12 hours/day, October to April)

- The patients in both groups were similar with respect to prognostic factors. YES

- All participants (patients, clinicians, outcome assessors) were unaware of group allocation. NO

- All groups were treated equally except for the intervention. YES

- Follow-up was complete (i.e. at least 80% for both groups). YES (99.5%)

- All patient-important outcomes were considered. YES

- The treatment effect was large enough and precise enough to be clinically significant. YES

Key Results: 3,668 children presenting to the emergency department were assessed for eligibility. There were 647 children randomized into the study (n=323 for half-strength apple juice/preferred fluids and n=324 for electrolyte solution). The majority of exclusions were because no research personnel were present to enroll the child (1,297). It was about evenly split between boys and girls and the mean age was 28 months. There were not differences between groups at baseline.

There were some other interesting baseline data:

- 90% had history of vomiting and >40% had a history of diarrhea

- Mean time to presentation was around 3:30pm

- Mean time to vomit onset and emergency department visit was 30hrs and for diarrhea around 25hrs

- Ondandstron was used in about two-thirds of cases

Treatment Failure: 16.7% half-strength apple juice and preferred fluid vs. 25.0% electrolyte solution

- Primary Outcome: Treatment failure

- 16.7% (95%CI 12.8%-21.2%) half-strength apple juice group and preferred fluid vs. 25.0% (95%CI 20.4%-30.1%) electrolyte solution group.

- NNT of 12 with half-strength apple juice and preferred fluids to prevent one treatment failure.

- Difference between groups was -8.3% (97.5%CI –infinity to -2.0) showing non-inferiority (p<0.001).

- That is better than the pre-specified non-inferiority margin of +7.5%.

- The experimental group (half-strength apple juice and preferred fluids) was also shown to be superior to the control group (p=0.006).

- Secondary Outcomes:

- Less intravenous hydration in the half-strength apple juice and preferred fluids group (0.9% vs. 6.8%) at index ED visit (p<0.001).

Overall this is a very well conducted randomized trial. Listen to the podcast to hear the full discussion with Dr. Crocco on the five issues identified.

1) Convenience Sample: They did not recruit patients consecutively. It was a convenience sample (12 hours/day, 6 days/week, October to April). The risk with convenience sampling is that the sample of patients included in the study may not reflective, or cannot be generalized, to the overall population presenting to the emergency department. The number one reason for exclusion was no research personnel present (1,297). We could not find in the manuscript or the supplemental material a clear idea of what time of day the research personnel were available.

2) Composite Outcome: They used a composite outcome consisting of a number of clinically relevant measures. There are risks of composite outcomes, specifically that the metrics may not all have the same clinical relevance. In this case, the composite outcome “treatment failure” included hospitalization or intravenous rehydration, unscheduled health care visit, protracted symptoms, cross over and weight loss or dehydration after index case. These individual components may or may not be equal in terms of relevance to the family and patient. In this composite outcome the most statistically significant difference was in intravenous rates.

3) Concealment: Allocation was concealed in the emergency department by having identical opaque bottles of rehydration fluid but not at home. Upon discharge, parents were given an opaque envelope with instructions for care at home, which included the revelation of which treatment arm the child was in, thus eliminating concealment at that time. This has the potential to induce bias into the study. It is hard to know in which direction the bias would deviate the results. Would knowing that your child is getting dilute apple juice or electrolyte solution make you more or less likely to seek care? Hard to know.

4) Clinical Dehydration Scale: They used the CDS in this study. There are a number of dehydration scales and for the purposes of research it is important to use one that is appropriately validated. Dr. Crocco generally uses clinical gestalt assessment, but encourages people to use what they feel is most appropriate for them and their patients given their environment and experience.

5) Non-Inferiority and Superiority: This was designed as a non-inferiority study. They demonstrated that dilute apple juice was not only non-inferior but also superior to an electrolyte solution. Watch for a whole SketchyEBM episode coming out on this issue.

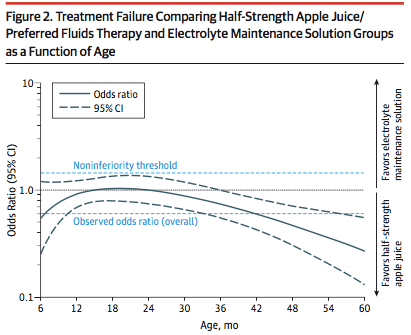

Anything else you want to say about this study Dr. Crocco? This study is a game-changer. The longstanding paradigm of managing children with gastroenteritis and minimal dehydration has been to use electrolyte solutions, such as developed by the W.H.O. in the 1960-70s. These fluids were originally developed for use in children in low-income countries with cholera outbreaks. Anecdotally these electrolyte fluids are poorly tolerated in kids due to poor taste. This study shows that, in a population of children from a high-resource country, half-strength apple juice and preferred fluids is better than electrolyte solutions for rehydration. Of interest, further analysis of the results showed that there was an interaction between age and effect with a greater effect noted in children over 24 months of age. (See Figure 2.)

Comment on author’s conclusion compared to SGEM Conclusion: We agree with authors’ conclusions. Half-strength apple juice and preferred fluids is a better choice for rehydrating children with mild gastroenteritis and minimal dehydration compared to electrolyte solutions.

SGEM Bottom Line: When advising parents with children with mild gastroenteritis and minimal dehydration, offering half-strength apple juice and preferred fluids compared to electrolyte solutions is a better choice.

Case Resolution: This girl is offered half-strength apple juice and tolerates this well in the emergency department. After a short period of time of observation in the emergency department, she and her family are sent home with adequate discharge information and detailed return to care instructions.

Clinically Application: In children with mild gastroenteritis and minimal dehydration, half-strength apple juice and preferred fluids is a better choice for rehydration.

What Do I Tell My Patient? I am going to get you some watered-down apple juice and see how well you are able to drink it. If you are able to keep it down without vomiting, we are going to send you home and your parents are going to continue to give you this fluid at home and preferred fluids.

Keener Kontest: Last weeks’ winner was Eben Clattenburg a 2nd year emergency medicine resident at Highland Hospital in Oakland, CA. He new Grosse Ile was the name of the Island close to Quebec City where the immigrants from Ireland had to spent some time to prevent locals from getting cholera and thyphus?’

Listen to the podcast for this weeks’ question. Send your answer to TheSGEM@gmail.com, The first correct answer will win a cool skeptical prize.

Other FOAMed:

- REBEL EM: Forget the PediaLyte and Just use Dilute Apple Juice in Mild Gastroenteritis

- Don’t Forget the Bubbles: An Apple Juice a Day?

- EM Cases Journal Jam 8: Dilute Apple Juice for Pediatric Gastroenteritis

You must be logged in to post a comment.