Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Date: August 30, 2023

Reference: Griffey et al. The SQuID protocol (subcutaneous insulin in diabetic ketoacidosis): Impacts on ED operational metrics. AEM August 2023

Dr. Suchismita Datta

Guest Skeptic: Dr. Suchismita Datta. She is an Assistant Professor and Director of Research in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the NYU Grossman Long Island Hospital Campus.

This is the last show for Season#11. It has been a great year with the addition of PedEM SuperHero Dr. Dennis Ren. We have some exciting news to cap off the end of this amazing year. Suchi will be joining the SGEM faculty as part of the Hot Off the Press team.

Case: A 28-year-old male with a history of type-1 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department (ED) with increase in thirst and light headedness. He is otherwise healthy. Blood glucose in triage is 489 mg/dl (27.2 mmol/L). Venous blood gas (VBG) shows an acidosis with a pH of 7.21. Electrolytes show a gap of 21. The patient’s symptoms begin to improve after initial intravenous (IV) fluid administration of one litre of 0.9% saline. The patient states he has had multiple “diabetic emergencies” in the past and usually ends up in the intensive care unit (ICU) on a drip. He is wondering, “Hey doc, do I have to go back to the ICU strapped to an IV pole?” The flow nurse has similar questions for you and wants to know if she should clear out a bed in the critical care bay so that the patient can have appropriate nursing requirements for an insulin infusion. Your resident is eager to go ahead and sign off on the diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) insulin order set and the ICU attending’s “Spidey senses” are going off. They are on the phone asking you if you already have another admission for them on this busy day. However, the ICU is full and the patient will likely be boarding in your ED for a bit before coming upstairs. Just as all this is happening, you notice how the waiting room is filling up and you can hear the sirens of approaching ambulances becoming louder. You take a deep breath, and you think to yourself…let the squid games begin.

Background: DKA is a common yet potentially fatal condition seen in patients with type 1 diabetes. It accounted for roughly 8.9 ED visits /1000 adults with diabetes [1]. DKA results in over 500,000 annual hospital days with estimated annual hospital costs of over $5 billion [2].

Dr. Nathan Kuppermann

Despite how common and expensive the management of DKA can be, we have only looked at it once on the SGEM. That was an episode covering the practice changing randomized control trial published in NEJM by Dr. Nathan Kuppermann from the PECARN Team for pediatric DKA [3]. They reported that the type of intravenous fluids (0.45% NaCl or 0.9% NaCl) or speed of infusion did not appear to make a clinically important difference (SGEM#255).

Because of the complexity of care around managing DKA, the typical approach is an insulin drip with ICU level of care for all degrees of severity. Increased resource utilization around this can prolong ED length of stay, especially in the context of a busy hospital or a global pandemic.

However, over the past 20 years, there is burgeoning evidence that fast-acting subcutaneous insulin analogs could be a potential treatment option for mild to moderate severity DKA including a 2016 Cochrane SRMA [4]. If proven to be a safe and effective management strategy, this would eliminate the need for an insulin drip and opens new options for management and disposition of DKA patients from the ED.

Using fast-acting subcutaneous insulin could streamline care in the ED and decrease the length of stay (LOS) in the department. This reduction in LOS is desirable for many reasons including overcrowding, prolonged wait times, and the availability of ICU beds for other critical patients.

Clinical Question: Can a patient with mild to moderate severity DKA be safely managed with subcutaneous fast acting insulin analogs on a non-ICU floor with blood glucose monitoring every two hours, and ultimately decrease ED length of stay?

Reference: Griffey et al. The SQuID protocol (subcutaneous insulin in diabetic ketoacidosis): Impacts on ED operational metrics. AEM August 2023

- Population: Non-pregnant, adults (18 years and older) who are presenting with mild to moderate [MTM] DKA

- Excluded: Pregnant patients, patient younger than 18, patients with concurrent infections, patients with active co-morbidities [ESRD, CHF, active use of immunosuppressants), concerns for myocardial infarction, altered mental status, need for surgery, or at the discretion of ED team if patient deemed to be too sick for the designated floor [which was an OBS floor run by hospitalist].

- Intervention: SQuID protocol – Sub Q insulin and admission to predesignated floor

- Comparison: MTM patients who receive traditional treatment during intervention period, MTM patients who received traditional treatment pre-intervention period, and MTM patients who received traditional treatment pre-COVID [three total cohorts of patients who received traditional treatment]

- Outcome:

- Primary Outcome: Impact of the SQuID protocol on ED length of stay [ED LOS] and ICU LOS.

- Secondary Outcomes: Fidelity to the protocol [ability to monitor with Q2H BG monitoring], and safety [need for rescue dextrose for hypoglycemia]

- Type of Study: A prospectively-derived quasi-experimental (pre–post) study done at one urban academic hospital in the USA.

Dr. Richard Griffey

This is an SGEMHOP episode, and it is my pleasure to introduce Dr. Richard Griffey He is a Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. He has a long-standing interest in patient safety and quality, including adverse event detection, health communication, ED operations, evidence-based imaging and implementation science. Dr. Griffey serves on the editorial board of Academic Emergency Medicine, as a reviewer for several major journals and he has held multiple leadership roles in the American College of Emergency Physicians’ (ACEP’s) Safety and Quality infrastructure. His work is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

SQuID Protocol

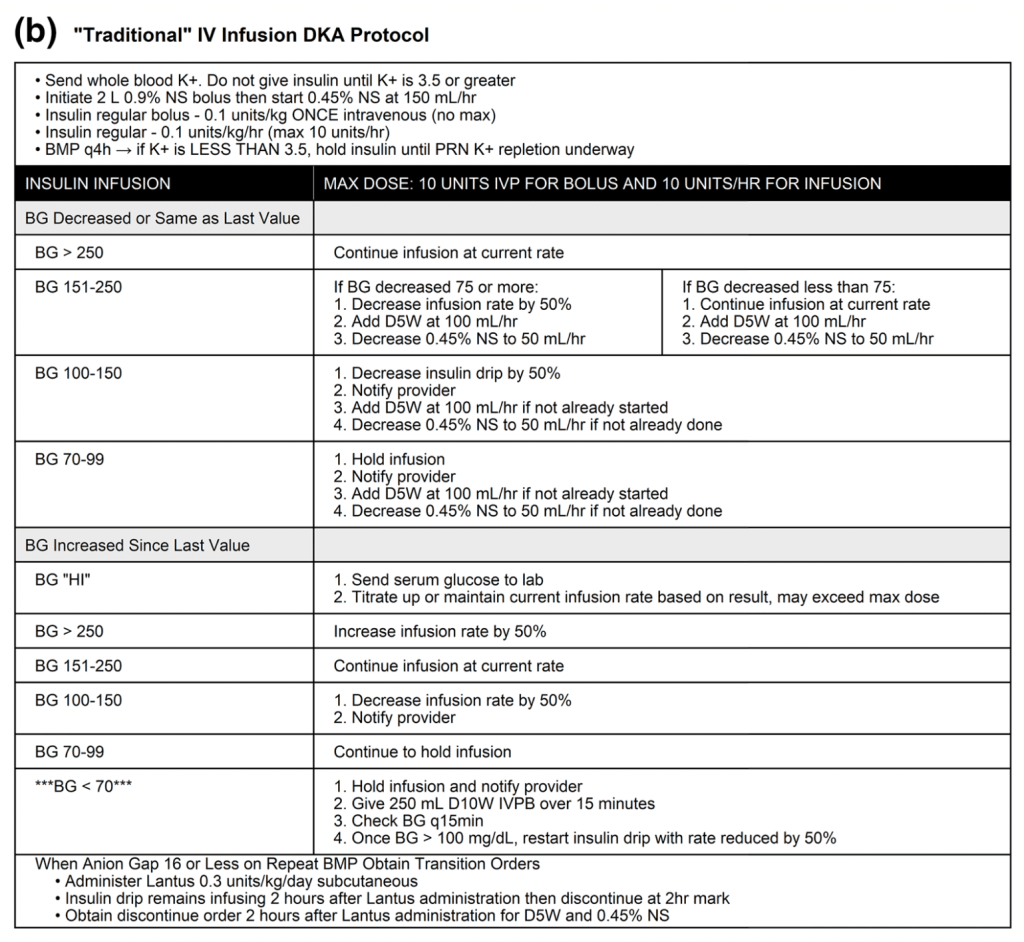

Traditional DKR Protocols

Authors’ Conclusions: “SQ fast acting insulin analogs for the treatment of MTM severity DKA is effective with equivalent safety to insulin drips, and is associated with decreased length of stay in the ED.”

Quality Checklist for Observational Study:

Quality Checklist for Observational Study:

- Did the study address a clearly focused issue? Yes

- Did the authors use an appropriate method to answer their question? No

- Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? Yes

- Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? Yes

- Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? Yes

- Have the authors identified all-important confounding factors? No

- Was the follow up of subjects complete enough? Yes

- How precise are the results? Fairly precise

- Do you believe the results? Yes

- Can the results be applied to the local population? Unsure

- Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? Yes

- Funding of the Study. This study was supported by a grant from the from the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation. Dr. Griffey is supported by grant 1 R01 HS027811-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Results: The included 177 patients with MTM-severity DKA (78 SQuID, 99 traditional). Of this cohort, 76 were admitted to an ICU. Among those admitted to a medical floor, 73 patients were managed on the SQuID protocol and 28 were managed on an insulin infusion. A total of 27 DKA patients with prolonged boarding in the ED were treated on their respective protocols and were ultimately discharged home from the ED. For historical controls they identified 163 MTM-severity DKA patients in the preintervention period (88 non-ICU) and 161 patients in the pre-COVID period (82 non-ICU).

Key Result: ED length of stay was statistically shorter in patients treated with SQuID protocol comparted to the traditional protocol and historic controls.

- Primary Outcome: Median ED LOS and ICU admission for SQuID vs comparison

- SQuID vs traditional during the study period (−3.0, 95% CI −8.5 to −1.4)

- SQuID vs preintervention period (−1.4, 95% CI −3.1 to −0.1)

- SQuID vs pre-COVID control period (−3.6, 95% CI −7.5 to −1.8)

- Decrease in ICU admissions across all MTM DKA patients was seen over time with no statistical difference between intervention period to pre-intervention and pre-COVID period

- Secondary Outcomes:

- Fidelity was measure as “high.” It was limited to tracking frequency of BG measurements with a goal to measure at Q2H or longer.

- No differences in safety between the SQuID and traditional pathways were observed

- Rescue dextrose was administered to two patients on the SQuID protocol and one on the traditional pathway

Listen to the SGEM podcast to hear Richard respond to our five nerdy questions.

1. Observational Study: You state this was a prospectively-derived quasi-experimental (pre–post) study. Another way to describe this would be an observational analytic study (CEMB). The semantics don’t matter because we can all agree that this was not a randomized control trial comparing SQuID to the traditional protocol. Why not just to an RCT?

2. Differences: Because this was not an RCT and you can see in figure 1 the differences in demographics between the cohorts. SQuID patients were 6 to 12 years younger than their comparison groups. It was also a 40:60 male:female split for the SQuID group compared to a 60:40 split for the control groups. While post-hoc adjustments can be made this indicates to us there are obvious measured differences between the groups and likely other unmeasured differences too.

3. Small Study: This is a relatively small study when looking at the primary outcome. Only 177 MTM-severity DKA patients in the study period (78 SQuID, 99 traditional cohort) to compare to some historic controls. Making things more difficult to interpret, 27 DKA patients had their entire management were boarded in the ED and discharged directly home. This does not help us answer the question of whether it is safe for these people to be treated on the medical ward of an in-patient unit.

4. Safety: While you properly conducting a power calculation aimed at the primary outcome of ED LOS using a one-sided Mann–Whitney U test, you appropriately recognize in your limitation section the study was not powered for safety. A friendly amendment would be to say that you did not find a “statistical” difference rather than saying no difference was observed. There was a difference in the two-point estimates (SQuID 7% vs traditional pathway 3.6%).

5. External Validity: We need to remember that you excluded patients with certain active comorbidities, concomitant acute medical illnesses, pregnant people or subjectively felt to be too sick for the floor. This really narrows down who the study can be applies to.

Another correctly self-identified limitation was the study location. It was performed at a single urban academic center in the USA. This is very similar to my practice environment but could be very different to others who listen to the SGEM. How this would apply to other urban centers, community hospitals, critical access hospitals and other healthcare systems outside the USA is unknown.

Comment on Authors’ Conclusion Compared to SGEM Conclusion: We generally agree with the authors conclusions.

SGEM Bottom Line: Managing patients with mild to moderate DKA outside of an ICU with fast acting subcutaneous insulin seems like a potential alternative while more data is needed from other sites to address efficacy and safety.

Case Resolution: After listening to the SGEM episode on the SQuID protocol, you share your evidence with your hospitalist colleague. He agrees to accept the patient to the floor and discusses his plan of glycemic control with the floor nurse. He documents the plan per the published protocol in detail and makes sure that all care team members are updated on the plan. You reassess your patient and let him know that you are initiating the SQuID protocol. He gets a little anxious at first, but you reassure him that it has nothing to do with the TV program. You let him know that since he is young, healthy, and without any other serious comorbidities, and has mild to moderate DKA, evidence suggests that subcutaneous insulin will likely be a safe alternative for him. He is happy to hear that he will not be chained to an insulin infusion.

Clinical Application: Consider taking this information on fast acting subcutaneous insulin to your next EM department meeting to see if you can start a conversation on whether a SQuID protocol could be implemented at your facility.

What Do I Tell the Patient? We found that today you are in mild to moderate DKA. There is emerging data to suggest that this kind of DKA can be managed on a non-ICU floor using subcutaneous insulin shots instead of the traditional insulin drip – known as the SQuID protocol. The SQuID study suggests that since you are both young and healthy, there is a good chance that this protocol will be both effective and safe for you. There is also good evidence to suggest that your length of stay in the emergency department will be less than the traditional route of treatment. There is a small chance that you may end up needing ICU anyway. What would you like to do?

Keener Kontest: Last weeks’ Dr. Steven Stelts. He knew nicardipine was patented in 1973 and approved for medical use in 1981.

Listen to the SGEM podcast for this weeks’ question. If you know the answer, then send an email to thesgem@gmail.com with “keener” in the subject line. The first correct answer will receive a cool skeptical prize.

Listen to the SGEM podcast for this weeks’ question. If you know the answer, then send an email to thesgem@gmail.com with “keener” in the subject line. The first correct answer will receive a cool skeptical prize.

SGEMHOP: Now it is your turn SGEMers. What do you think of SQuID protocol? Tweet your comments using #SGEMHOP. What questions do you have for Richard and his team? Ask them on the SGEM blog. The best social media feedback will be published in AEM.

Remember to be skeptical of anything you learn, even if you heard it on the Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine.

References:

- Prevention CFDCA. National Diabetes Statistics Report: coex- isting conditions and complications. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 28, 2021. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/coexisting -conditions-complications.html

- Desai D, Mehta D, Mathias P, Menon G, Schubart UK. Health care utilization and burden of diabetic ketoacidosis in the U.S. over the past decade: a nationwide analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8):1631-1638.

- Kuppermann N, Ghetti S, Schunk JE, Stoner MJ, Rewers A, McManemy JK, Myers SR, Nigrovic LE, Garro A, Brown KM, Quayle KS, Trainor JL, Tzimenatos L, Bennett JE, DePiero AD, Kwok MY, Perry CS 3rd, Olsen CS, Casper TC, Dean JM, Glaser NS; PECARN DKA FLUID Study Group. Clinical Trial of Fluid Infusion Rates for Pediatric Diabetic Ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 14;378(24):2275-2287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716816. PMID: 29897851; PMCID: PMC6051773.

- Andrade-Castellanos CA, Colunga-Lozano LE, Delgado-Figueroa N, Gonzalez-Padilla DA. Subcutaneous rapid-acting insulin an- alogues for diabetic ketoacidosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD011281.

You must be logged in to post a comment.