Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: RSS

[display_podcast]

Date: March 26th, 2015

Guest Skeptics: Dr. Suneel Upadhye (BEEM Group) and Dr. Tiffany Osborn (ProMISe Author)

Suneel is an Associate Clinical Professor Emergency Medicine at McMaster University and Associate Member of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics. He is also the Chair CAEP standards committee and a sepsis researcher.

Tiffany is the second author on the ProMISe Trial. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Surgery and the Department of Emergency Medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

Case: You see a 62 year-old man sent from a nursing home with a three day history of a productive cough, intermittent fevers and today is a bit confused. The transfer notes include a history of congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gout, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and mild dementia. His emergency department vitals are as follows: Temperature 39.1C, heart rate 103, blood pressure 115/100, respiratory rate 26, oxygen saturation is 92% on room air, and capillary blood sugar is normal.

Question: Does an emergency department patient with septic shock need aggressive EGDT or is “usual” resuscitation just as good?

Background: Sepsis can be defined as a “clinical syndrome complicating severe infection characterized by inflammation remote from the site of infection. Dis-regulation of the inflammatory response can lead to multiple organ dysfunction.”

- Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) Criteria:

- A temperature over 38C or less than 36C

- A heart rate over 90 beats/min

- A respiratory rat e over 20 breaths/min or PCO2 less than 32mmHg

- A WBC count less than 4,000 or over 12,000 or greater 10% immature forms

- Sepsis: At least two of the four SIRS + infection.

- Severe Sepsis: Sepsis + hypotension and end organ failure

- Hypoxia, renal failure, hepatic failure, coagulopathy, hypotension, lactate greater than 2 mmol/l

- Septic Shock: Severe sepsis and hypotension refractory to fluid treatment or lactate greater than 4 mmol/l

Previous SGEM Episodes on Sepsis:

- SGEM#44: Pause (Etomidate and Rapid Sequence Intubation in Sepsis)

- SGEM#69: Cry Me A River (Early Goal Directed Therapy) ProCESS Trial

- SGEM#90: Hunting High and Low (Best MAP for Sepsis Patients)

- SGEM#92: ARISE Up, ARISE Up (EGDT vs. Usual Care for Sepsis)

Reference: Trial of Early, Goal-Directed Resuscitation for Septic Shock. NEJM March 2015.

- Population: Adult patients presenting to the emergency department with early septic shock (SIRS 2+ criteria with refractory sBP<90mmHg despite fluid resuscitation 1L within 6 0minutes, or hyperlactatemia >4mM). Patients recruited from 56 hospitals (approximately 25% of total hospitals) in England (29% teaching hospitals).

- EXCLUDED if age<18yo, pregnant, primary acute diagnosis (stroke, acute coronary syndrome, congestive heart failure, status asthmaticus, arrhythmia, seizure, over-dose, burn/trauma), unstable GIB, need immediate surgery, history of AIDS, do not resuscitate/other advanced directives restricting resuscitation, contraindications to line placement/blood transfusions, transfer from another in-hospital setting, not able to commence within 1hr emergency department arrival or complete 6hr protocol, physician discretionary exclusion.

- Intervention: Early goal-directed therapy (EGDT). Note – all patients received antibiotics before randomization.

- Control: “Usual care” including monitoring, investigations and treatment as determined by treating clinician(s)

- Outcome:

- Primary Outcome: 90 day all-cause mortality.

- Secondary Outcomes: SOFA Scores (6, 72hrs), organ support (cardiovascular, respiratory, renal) in critical care up to 28days, length of stay (emergency department, intensive care unit, hospital), all-cause mortality 28d/hospital /1year, survival duration, health-related quality of life (HRQOL, measured on EQ-5D-5L), resource usage, costs at 90d and one year.

Authors’ Conclusion: “In patients with septic shock who were identified early and received intravenous antibiotics and adequate fluid resuscitation, hemodynamic management according to a strict EGDT protocol did not lead to an improvement in outcome.”

Quality Check List for Randomized Control Trials:

Quality Check List for Randomized Control Trials:

- The study population included or focused on those in the ED. Yes

- The patients were adequately randomized. Yes

- The randomization process was concealed. Process – Yes, Allocation – No

- The patients were analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized. Yes

- The study patients were recruited consecutively (i.e. no selection bias). Yes

- The patients in both groups were similar with respect to prognostic factors. Yes

- All participants (patients, clinicians, outcome assessors) were unaware of group allocation. No

- All groups were treated equally except for the intervention. Yes

- Follow-up was complete (i.e. at least 80% for both groups). Yes

- All patient-important outcomes were considered. Yes

- The treatment effect was large enough and precise enough to be clinically significant. No

Key Results: This was a parallel arm superiority trial, 1:1 randomization in permuted blocks of 4/6/8. 1260 patients needed for sample size, 1243 completed trial (>98% follow-up) for primary outcome of interest. Baseline characteristics well matched in both arms, including infection sources.

Only 1/3 patients screened were successfully recruited with poor recruitment on weekends and nights. Recruitment rate of eligible was similar to the two other trials (note: recruitment by day-of-week/time-of-day was not reported by the other two trials). Lower recruitment at weekends and nights indicates the challenges faced in conducting emergency and critical care research.

The economic evaluation was based on 2012 GB pound/US dollar values. Cost effectiveness determined on threshold willingness to pay for QALY gains as per NICE guidelines (GBP 20,000 / USD $28,430 per QALY).

- ED Protocol adherence (0-6hrs):

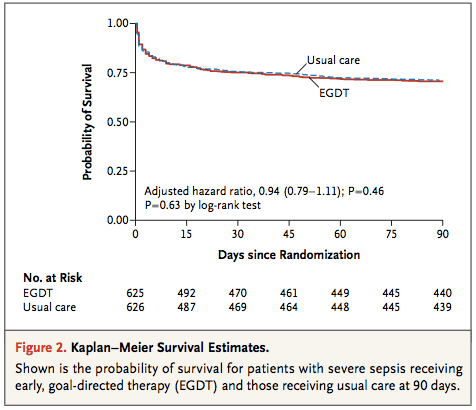

Primary outcome from ProMISe Trial: No statistically significant difference in 90d all cause mortality (EGDT 29.5% vs. Usual Care 29.2%)

Relative risk in the EGDT group, 1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.85 to 1.20; P=0.90 for an absolute risk reduction in the EGDT group of −0.3 percentage points (95% CI, −5.4 to 4.7)

Secondary Outcomes:

- Mortality:

- No difference – 28 days: 24.8% vs. 24.5%

- No difference – Hospital discharge: 25.6% vs. 24.6%

- Median length of stays (LOS):

- No difference – ED LOS: 1.5hrs vs. 1.3hrs

- ICU LOS: 2.6 days vs. 2.2 days

- No difference – Hospital LOS: 9d vs. 9d

- Days free from life support:

- No difference – Cardiovascular 37.0% vs. 30.9%, Respiratory 28.9% vs. 28.5%, Renal 14.2% vs. 13.2%

- Quality of Life:

- No difference – Health related quality of life

- No difference – QALY up to 90d

- Expense/Cost of EGDT vs. Usual Care?

- No difference – Average costs up to 90d: $17,647 EDGT vs. $16,239 UC

- It was about £1,000 more to do EGDT – mostly associated with the ½ day increased LOS in the ICU

- Harm:

- No difference in serious adverse events: 4.8% vs. 4.2%

The trifecta on EGDT for sepsis has been completed. This is the final nail in the coffin for EGDT for adult septic shock in the emergency department.

A nail with caveats. From a population standpoint, in institutions where usual care entails a system of consistent early identification (recognized with 1.5 hr, randomized in under 3 hours from presentation). Early IV fluids. Remember that about 2 liters prior to randomization. Early antibiotics (had to be started prior to randomization – median within 3 hours from presentation). Early lactate measurement. When this is your usual care, you can expect similar outcomes as ProMISe.

We still need to further explore usual care in our study. For example, what is unclear is if there are certain populations that may benefit from the other components of the protocol and this will be worked out in a combined analysis among the three trials.

These results mirror the earlier results of the ProCESS (US) and ARISE (Aus/NZ/Finland) trials comparing EGDT vs. “usual care” protocols, and showing no differences between any of the arms worldwide. Again, trial planners agreed to harmonize the endpoints of all 3 trials, so future metaanalyses should confirm these results using individual patient data.

The failure to reproduce the original 2001 Rivers/early EGDT results in all 3 trials likely reflects the increased attention and aggressive treatments (albeit non-invasively) that most ED physicians now use worldwide in treating septic shock patients. It is now clear that an expensive and invasive care for these patients is not necessary.

Given the attention focused on sepsis, it seems highly unlikely that usual resuscitation has not improved in the 10-15 years since the study by Rivers and colleagues.

An important consideration, however, when interpreting the results from ProMISe (and those from the harmonised trilogy of trials including ProCESS and ARISE) is that the patients recruited to ProMISe were identified early and received a median of 2L of IV fluids and antimicrobial drugs prior to randomisation. Then, in this group of patients, subsequent, algorithm-driven EGDT (as defined by the six-hour resuscitation protocol from the study by Rivers and colleagues) including continuous central venous oxygenation monitoring did not lead to an improvement in outcomes and increased the costs of care.

Of note, this trial did calculate utility measures for HRQOL using a validated tool, and found that EGDT was more expensive than usual care (not significantly so), and the incremental net benefit of EGDT over usual care was negligible. It is rare to have simultaneous real-time economic evaluations done in large randomized control trials, so when they are done (and done properly as it was here), the results are even more informative.

There have been some other great FOAMed reviews of the ProMISe trial:

- Salim Rezaie at REBEL EM: The Protocolised Management in Sepsis (ProMISe) Trial

- Richard Body at St. Emlyn’s Blog: The ProMISe Study – EGDT RIP?

- Ryan Radecki at EM Lit of Note: Early Goal-Directed Waste For Sepsis

- The Bottom Line: Trial, of Early Goal-Directed Resuscitation for Septic Shock

Our Conclusions Compared to Authors’: We agree with the ProMISe authors conclusions. However, as in previous trials, this is NOT a refutation of any protocolized care, but only EGDT in its original 2001 version (Rivers NEJM). Every study group and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign still recommend the use of sepsis protocols that emphasize:

- Early recognition

- Copious IV crystalloid resuscitation

- Lactate screening

- Targeted (or at least broad-spectrum) antibiotics

The SGEM Bottom Line: There is no need to provide invasive expensive EGDT in the emergency department for septic shock patients.

Case Resolution: Having recognized the sepsis potential of this patient and confirming a high lactate, you initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics for what is most likely a clinical pneumonia. You give aggressive fluid resuscitation with IV normal saline or ringers lactate. Then call your consultant to arrange admission to the intensive care unit.

Clinical Application: If it is 02:00 and you are working in a single coverage emergency department you can start with IV fluids, antibiotics and lactate measurement. If you have volume refractory shock requiring vasopressors, then most guidelines support administering them through a central line. Given that about half of the usual care group received central lines within about 2 hours after being randomized indicates that emergency department providers are both decisive and capable when they feel central lines are needed.

What Do I Tell Patients? You have a serious infection. We are going to give you lots of intravenous fluids, start antibiotics, measure something called a lactate level that can help us tell how sick you are and if you are responding to treatment and we are going to admit you to hospital.

Keener Kontest: Last weeks winner was Dr. Chris Wood. He knew the Canadian Version of PECARN is called PERC (Pediatric Emergency Research Canada).

Listen to the podcast to hear this weeks keener question. If you know the answer send me email to TheSGEM@gmail.com with “keener” in the subject line. The first person with the correct answer will receive a cool skeptical prize.

You must be logged in to post a comment.