Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: RSS

[display_podcast]

Date: April 28, 2013

Title: This is Spinal Tap (Lumbar Punctures)

Case Scenario: A 66YO man presents with a 48hr history of fever, lethargy and headache. No significant past medical history. On physical examination he has a temperature of 38.8C, GCS 15, stiff neck on flexion and no rash. Urinalysis and CXR are normal. Laboratory testing reports an elevated WBC with a left shift. You decide he needs a lumbar puncture (LP) to check for meningitis.

Question: How to perform the lumbar puncture

Reference: Straus SE, Thorpe KE, Holroyd-Leduc J, “How do I perform a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis?” JAMA 2006

- Population: Adults patients undergoing diagnostic lumbar puncture (15 studies included)

- Intervention: Variations in techniques including positioning, needle type, stylet technique and post-procedure care

- Outcome: adverse post-LP patient events

- Analyses: LRs with 95% CI

Background: The first lumbar puncture was described by Quincke in 1891 to sample the cerebral spinal fluid. It has been used since as a diagnostic tool to evaluate the CSF for evidence of things including infection and subarachnoid hemorrhage. It was only a few years later that post LP headache was described in 1899 by Bier. While headaches are a common complication of LPs there are a number of rare adverse events: cerebral herniation, intracranial subdural hemorrhage, spinal epidural hemorrhage and infection.

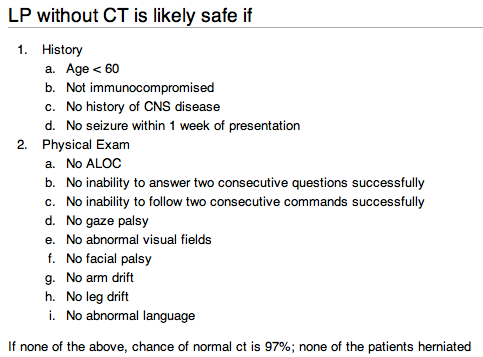

A concern that often comes up in these cases is whether or not a CT needs to be done prior to performing the LP. This review article states that there is no evidence supporting universal neuroimaging prior to LP. They suggest the use of clinical judgement but that is not defined well. The two references given are Gopal et al 1999 and Hasbun et al 2001.

Gopal (n=113) had internal medicine residents not emergency physicians examine patients. The sample population had a median age of 42 with 36% immunocompromised and 46% had altered mentation.

Hasbun (n=301) had emergency physicians or general internist evaluate the patients. The mean age was 40 with 25% being immunocompromised. Of the 301 only 235 got CTs prior to LPs.

Neither of these two studies have been validated prospectively in other independent populations.

This podcast will not be discussing the diagnostic accuracy of LP for meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage. The concept of whether or not you need to do an LP post CT to rule out a SAH has been debated lately (Newman’s 700 Club). SmartEM did a good podcast on this topic already.

Results:

Operator Experience: No randomized studies, little evidence from lesser-quality studies to indicate any significant effect from experience.

Positioning of Patient: Unable to identify studies that evaluated the success of LP with different patient positions or the impact of patient positioning on the risk of adverse events. Note is made that maximal interspinous distance is achieved in the seated- with-feet-supported position from an n=16 physiologic measurement study.

Number of attempts: Nonsignificant increase (ARI 4.9%; CI: -13% to 3.4%) in risk of requiring 2 or more attempts when an atraumatic needle is used. No increased risk of backache despite this.

Needle Choice: Suggestion of (nonsignificant) decrease (ARR 12.5%, CI: -1.72% to 26.2%) in headache among patients in which an atraumatic needle is used (Figure 2), statistically significant heterogeneity primarily due to the inclusion of one small 1993 study. Single study, n=100, demonstrated a significant reduction in risk of headache (ARR 26%; CI: 11%-40%) with a 22 gauge Quincke needle instead of a 26 gauge Quincke needle.

Stylet Reinsertion: single study, n=600, concluded reduced risk of headache when stylet was reintroduced before needle withdrawal (ARR 11%; CI 6-5%-16%) but no details on randomization or blinding was available.

Bed rest post-LP: Four studies, n=717, no significant heterogeneity. Decrease in risk of headache with immobilization was nonsignificant (ARR 2.9%; CI: -3.4% to 9.3%)

Supplementary Fluids: No convincing evidence found.

Sudlow CLM, Warlow CP. Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD001790. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001790.

Cochrane Conclusion: There is no good evidence from randomised trials to suggest that routine bed rest after dural puncture is beneficial. The role of fluid supplementation in the prevention of post-dural puncture headache remains uncertain.

Authors Conclusions: “These data suggest that small-gauge, atraumatic needles may decrease the risk of headache after diagnostic LP. Reinsertion of the stylet before needle removal should occur and patients do not require bed rest after the procedure. Future research should focus on evaluating interventions to optimize the success of a diagnostic LP and to enhance training in procedural skills.

BEEM Bottom Line: The following procedures may decrease the risk of post-LP headache:

- Small-gauge atraumatic needles

- Reinsertion of the stylet prior to the removal of the spinal needle

- Mobilization of patients after completing the LP

Case Resolution: You perform a successful LP and send off the CSF to the lab for analysis to rule out meningitis.

KEENER KONTEST: There was no keener kontest question last year with the Boston Marathon episode.

Be sure to listen to this weeks podcast for another chance to a cool skeptical prize. Email your answer to TheSGEM@gmail.com. Use “Keener Kontest” in the subject line. First one to email me the correct answer wins.

Follow the SGEM on twitter @TheSGEM and like TheSGEM on Facebook.

Remember to be skeptical of anything you learn, even if you heard it on The Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.